FCPAméricas Blog

Latin America’s Most Common Reaction to the FCPA

7.24.2015

Over the years, I have learned to count on a common reaction when discussing FCPA compliance in Latin America – “Well, you have corruption in the United States too.”

Over the years, I have learned to count on a common reaction when discussing FCPA compliance in Latin America – “Well, you have corruption in the United States too.”

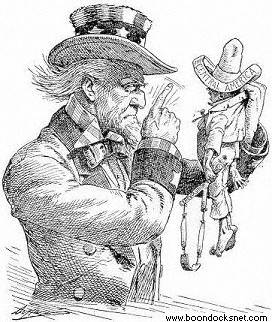

Latin Americans are surprised to hear that the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions address only foreign bribery – the payment of bribes to non-U.S. government officials. They often see the law as wrongly targeting foreigners, reflecting a lopsided approach to addressing corruption. To some, the FCPA demonstrates a U.S.-centric view of the world, suggesting that bribery is not a problem in the United States and is only an issue outside of its borders.

I have learned to address this viewpoint in a variety of ways.

- It is true, we certainly do have corruption in the United States. U.S. politicians are regularly caught committing such acts. Louisiana Congressman William Jefferson hid his stack of cash from kickbacks in his freezer. California Congressman Duke Cunningham lived rent-free on a yacht gifted by a defense-contracting firm. Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich attempted to sell the U.S. Senate seat vacated by President Barack Obama, and Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell and his wife accepted more than US$135,000 in gifts, travel, and low-interest loans from a dietary supplement manufacturer. However, the United States also has strong domestic bribery laws to address these types of local bribery issues. The fact that the U.S. Congress created the FCPA to apply only to bribes paid to officials from other parts of the world does not suggest that preventing domestic bribery is not addressed forcefully under U.S. law.

- Indeed, corruption exists everywhere, no matter the country. Only, some have done a better job of addressing it. Countries with stronger government institutions find more effective ways of criminalizing public corruption and penalizing the culprits. The result is lower levels of impunity for those who choose to give and receive bribes. When the calculation changes of getting caught, behavior tends to change.

- To be sure, no matter how stringent a country’s anti-corruption laws, bribery cannot be prevented one hundred percent of the time. The more relevant question is how a company, or a country, responds to the practice. Is bribery something that is institutionalized, or treated as an exception to the norm? When bribes are offered or requested, do the people involved feel threatened by the possibility of getting caught, or do they commit such acts with a sense of impunity, or even justification? Perhaps the answers to these questions are a differentiator between a country like the United States, where corruption is seen more as the exception, and many parts of Latin America, where a bribe might not be out of the norm.

- People in Latin America will understandably ask why lobbying in the United States is not considered a form of bribery. Indeed, it is hard to argue with the proposition that egregious lobbying has become commonplace in our country. By some, the practice certainly could be seen as an institutionalized form of corruption. The difference between lobbying and illicit bribery, however, is that many forms of lobbying common in our political process have been approved through a democratic lawmaking process. Elected representatives have decided that certain forms of paid political influence are acceptable, legitimate, and legal. Furthermore, these types of payments are generally regulated. In this respect, lobbying differs from rampant and unlawful corruption that is unlawful.

This is a complicated and nuanced discussion to have in Latin America. But it is an essential one to have if FCPA compliance efforts are to be seen as legitimate, worthwhile, and not one-sided. It is important to making compliance work in the region.

The opinions expressed in this post are those of the author in his or her individual capacity, and do not necessarily represent the views of anyone else, including the entities with which the author is affiliated, the author`s employers, other contributors, FCPAméricas, or its advertisers. The information in the FCPAméricas blog is intended for public discussion and educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide legal advice to its readers and does not create an attorney-client relationship. It does not seek to describe or convey the quality of legal services. FCPAméricas encourages readers to seek qualified legal counsel regarding anti-corruption laws or any other legal issue. FCPAméricas gives permission to link, post, distribute, or reference this article for any lawful purpose, provided attribution is made to the author and to FCPAméricas LLC.

© 2015 FCPAméricas, LLC

Post authored by Matteson Ellis, FCPAméricas Founder & Editor

Comments

Comments

August 4th, 2015 at 1:50 pm

Many would argue, however, that the fact that lobbying is legal and ordained by laws created by the very individuals benefiting from them is a form of institutionalized corruption – more institutionalized than every day corruption you see in Latin America.